We are familiar with the economics and mechanics of education because these are often fiercely debated but the idea of schooling can still be improved if we initiate more conversations about the philosophy or philosophies that sustain it. Simply put, we should endeavor to give better answers to the question ‘Why do we need to go to school?’

It can be argued that the question is unnecessary since everybody is united in the goal of providing universal education. Besides, education is a human right and it is guaranteed by the constitution of almost all countries in the world.

But the question is not simple; rather it is deceptively simple, and it is necessary.

What are the ‘known knowns’ of education: that it promotes the social good, that it leads to social mobility, and that it nurtures individual talent. But education also has its ‘known unknowns’: that education can make us rich, or that at least it can help us get decent employment, and that it rewards those with talent and dedication.

The first set is publicly admitted and popularly endorsed; the second is privately affirmed. There are those who equate the first with the second and so they have no problem identifying with either category. The first is too broad and seldom elaborated which leads many to interpret the second as the particulars of the noble goals of education. This is wrong. But this thinking is rarely contested so we grew up believing that individual and social misfortunes are mainly caused by an obscene absence or lack of education. This is not entirely incorrect because education is an important factor that can address multiple social ills. The problem, however, is reflected in our other unrealistic expectations about what the schooling process can deliver.

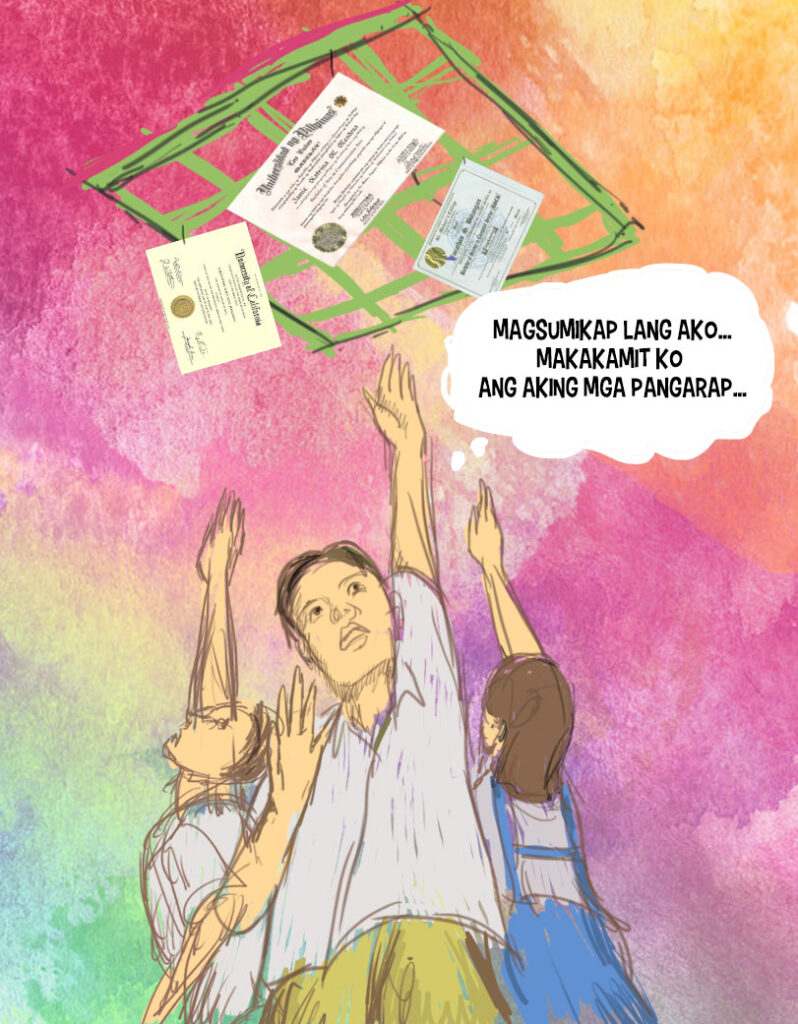

That formal education as we know it enjoys our utmost confidence is unsurprising considering that we are constantly bombarded with messages that extol its value. For example, we have movies that simplify the correlation of scholastic achievement and career advancement, politicians who preach the centrality of education in the social reform agenda, overpaid technocrats who bemoan the disconnect of the academic and corporate sectors, and the most persuasive of them all: the hard work and sacrifice of families who financed the schooling of their children, a gesture of love and unforgettable proof of our faith in the power of education.

What exactly is wrong with these obviously benign motives? Well, to put it mildly, they narrow and distort the humanistic goals of education.

The desire to be rich is an old vice but the aspiration to be rich by acquiring a university diploma is a modern thing. It is an unhealthy impulse because it contravenes ALL philosophies of education. To cultivate wisdom actually requires a negation of materialistic pursuits. An educated person rejects transience as he or she seeks the truth about our existence. If the goal is to possess things, it is false education. In other words, we should not justify the hoarding of tangible goods by claiming that it is the consequence of academic excellence.

But is it wrong to pursue education so that we can acquire the skills that give us the opportunity to seek gainful employment? Again, this is a modern concept. Admittedly, a major aspect of formal education includes the training of individuals on how to properly live in the future world of work. Indeed, a school is a fun place to learn the trades in the company of friends.

But education should be more than just about job preparation. After centuries of preserving the idea of the university and after the painstaking struggle of transferring knowledge from one generation to another, should we readily accept the assertion that the function of modern education is to support the needs of the business sector? That the main role of schools in society is to promote efficiency in the employee-employer relationship?

What happened to the grand idea of producing philosopher-kings? What about citizenship? A school is more than just a repository of knowledge, it represents human civilization. It is where children study the classics, experiment with new concepts, investigate the reality of the present, and sketch the blueprint of the future. The school is supposed to be a disruptive force in society.

The radical campaign to institutionalize mass education succeeded in the 20th century but it was hijacked by corporate interest. Children of the working classes were provided with a specific set of values in schools that reflected the worldview of the ruling elite. Innovation was praised as long as it did not threaten the political order. Discipline and conformism were formally and indirectly endorsed at the same time.

Critical pedagogy was ignored in favor of practical objectives to help citizens confront the various challenges of modern living. Schools maintained its social character but overall its political role tended to favor conservative interest.

The capitalist principle of competition was transplanted in schools, which perverted the dynamism of the education system. As transmitters of official knowledge and incubator of progress, schools are viewed as an institution that can uplift the economic conditions of the poor. Unfortunately, schools in the neoliberal age performed this role by teaching children that competition is the key to success. The schools as ‘sorting machine’ elevated individual achievement as superior over other desirable social goals. Who can blame parents for wanting their children to live the good life? But once again, individualism prevailed by spreading the propaganda that we can escape poverty by focusing first on self-improvement. Instead of fighting the evils of society as a collective body, we abandon that crucial task to prominent, educated individuals. Instead of finding satisfaction in our participation in a group effort, we prefer to indulge in self-praise.

A college graduate is recognized for possessing the proper skills and attitude that made him or her successful. What is overlooked is the social capital that was invested that allowed the graduate to finish schooling. It is natural to feel good about ourselves but it is a mistake to assume that we completed our formal education without needing any subsidy or assistance from various social bodies.

Believing that we survived and surged ahead of others mainly by relying on our talent and perseverance, we flaunted this perspective that reproduced the superficial thinking that schools exist to breed a few outstanding individuals.

But schools can do more than merely transform us all into highly-skilled, productive, and obedient workers. Through schooling, we can still celebrate our humanity. We can still aim for holistic education to develop our full potential as a person. We can still learn to be critical citizens whose individuality is affirmed without undermining the rights of others. Collective work, not destructive competition, can still become the norm.

First, we must cease to view schools as a politically-neutral space.

Second, we must not divorce theoretical knowledge, which is obsessively protected in the academe, from practical politics.

Third, we should develop pedagogical practices that enhance our full humanity and promote collective values.

Fourth, we should build schools whose mission is to challenge tradition, and these inventive institutions should be given the freedom to implement their vision in society.

Comments are closed.