The year 2017 was marked by changes mostly confined to political violence.

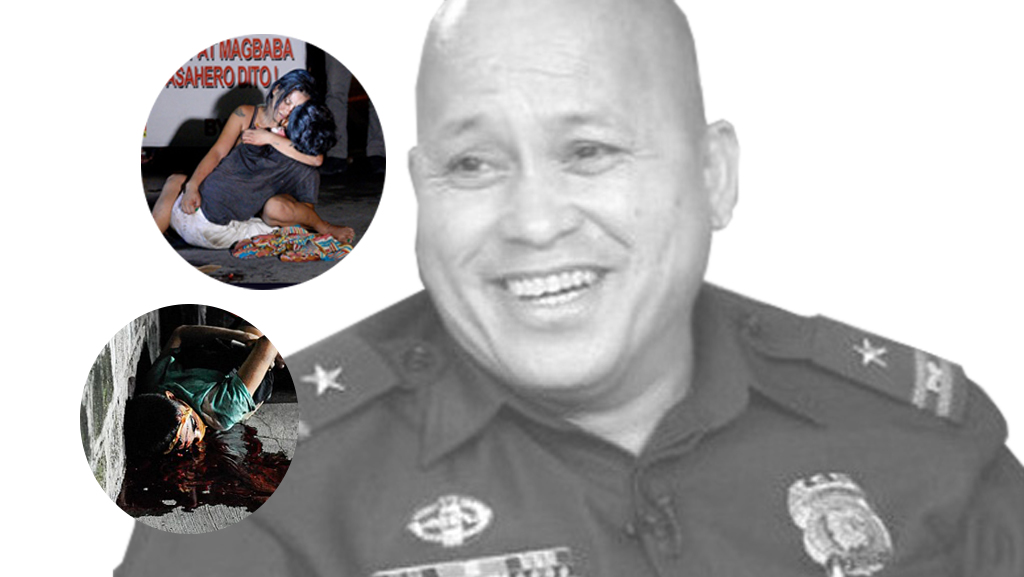

A likely new political order was initially embraced with hope turned anguish and disillusion. The pitilessness of extrajudicial killings and the morbid verbosity of the president turned the international spotlight on the Philippines second to the showy, destructive unintelligence of Trump’s administration.

Among the notable changes was the reaction of a good part of the population to the war on drugs. A reaction or perception that is painfully disturbing and alienating from elementary morality. The war on drugs was (is still being) singularly justified by common citizens with the claim: “Kung di ka adik wala ka dapat ikabahala (If you’re not an addict, you have nothing to worry about).”

In discussions and debates, concerned citizens and critics of the government are often met with this seemingly sincere and innocent rebuff by devoted supporters of the government. Observing the commentaries of Duterte supporters on human rights in social media they all appear equally to be expressing the same sentiment. Anyone who’s expressed his/her concern for the disturbing violence of the war on drugs has on more than one occasion heard that phrase.

To take the argument at face value seems to clear up the confusion and unnecessary worry. But as we reflect deeper and take the claim into a broader context we discover that what seems to pass as an innocent remark denotes, roughly, a justification of what is legally questionable and morally unjustifiable. Now I do not suppose that those who support the case are intrinsically indifferent to bloodshed, they do so, I believe, out of ignorance or bad faith.

Here are some thoughts to deconstruct the nature of the claim: “Kung di ka adik wala ka dapat ikabahala (If you’re not an addict, you have nothing to worry about).”

1.) The claim suggests that non-addicts, like the wonderful supporters of our present leader, are entitled to be free from the burden of worrying and caring for others especially the poor who out of degrading poverty take to selling and using drugs to confront the misery of life.

The Jamaican National Council on Drug Abuse noted:

“Drug use and addiction have no single cause but the risk factors for drug use include poverty. A person in an impoverished situation may abuse drugs or alcohol as a way to cope with the dangerous environment she lives in, a way to deal with her financial stresses or a way to cope with physical or emotional abuse. Many times, drugs and alcohol are easily accessible in impoverished neighborhoods where some people actually sell drugs in hopes of overcoming poverty.”

Non-addicts should be worry-free because there’s the police, the hand of justice, to take care of things; and supporters blindly believe that the police are immune to errors, mistakes, accidents, and the abuse of power. Thus, those who perished in the hands of the police like Kian Delos Santos and others deserved their fate.

A realistic appraisal of evidence studied by a number of human rights organizations (along with the accessibility of CCTV footage) discloses the fact that not even a drug-clean person is free from the police’s abuse of power.

2.) The claim paints the grotesque idea that all addicts must be branded as criminals. Thus crime is tantamount to police operation. That is the argument of the powerful.

But if most of police operation is centered in the poor communities it follows that the majority of addicts are poor. If the poor are addicts then they are criminals and poverty is their greatest crime.

The claim seems to justify the barbaric method of dealing with drugs by police operation as though no other peaceful and compassionate methods are in existence.

By police operation the context is clear: brutal and humiliating drug raids in the poor areas, frequent shootings and killings and endless arrests, overcrowded prisons, traumatized communities, resentful citizens, bereaving families… And the problem has not been solved in any constructive way.

The term “war on drugs” is quite problematic if not puzzling. There are a number of reasons for this: one of which is the fact that a great part of the war, if not all of it, was waged in poor territories. Police patrols seem to have bypassed the rich suburbs, the luxurious areas of the upper class as though implying that the rich are clean and innocent. One wonders why.

3.) The claim also serves as a good excuse to avoid crucial issues that aggravate the problem of drugs.

Corporate media keep on blabbering about the surface problem of drugs but rarely delve into issues like dehumanizing poverty, demoralizing unemployment, landlessness, corruption, migration, lack of healthcare, debased educational system…

Corporate media biasedly focus on the criminal aspect of drugs, narrowing the spectrum of the debate, putting drugs at the center of all social malaise. The debate never goes as far as to ask a very simple question: why do people, particularly the poor, resort to the trade and use of drugs?

Media misrepresentation obscures the fact that the drug crisis is an accumulated effect of multiple social ills. Instead the media bombard us with attention-grabbing headlines accompanied by photographs and videos of dead victims which only adds to the humiliation and degradation of the situation of the poor.

This media narrow-mindedness and sensationalism is responsible for an misinformed public (especially a public that excessively depends on TV news for information) and for mobilizing fanatics behind a bloody campaign. One way to cure this disease of ignorance is to read authentic resources: human rights documents, alternative news outlets, independent journals, and good old books.

As the bloody war on drugs moves on with no end in sight, the year 2018 presents more worry for concerned individuals and communities. To worry, to care is to reclaim our humanity. It is incumbent on us to peacefully and intelligently provoke the government (and its many supporters) to view the problem of drugs in a different perspective.

If this nation has a minimum respect for life we should ensure that our government invest in life-enhancing projects rather than perpetuating the untenable, expensive, inhumane drug policies. The government can start by diminishing the power and role of the police in the program.

The Philippines can learn much from countries like Portugal, the Netherlands, Uruguay, (recently) Norway, and some states of North America which have reformed their drug policies from punishment to treatment, from the justice system to the health system with significant results. We should not be led to believe that there are no other alternatives than the awful police operation because there are– there are more just, more dignified, and informed by science ways to deal with the crisis which has already claimed too many lives.

Yes, we should worry.

—

Carlo Rey Lacsamana is a Filipino, born and raised in Manila, Philippines. Since 2005, he has been living and working in the Tuscan town of Lucca, Italy.