“Buksan ang pag-iisip,

Tayo’y likas na scientist!”–Sineskwela opening theme

Recent news about Project NOAH’s reported struggles highlights the sorry state of our country’s science and technology sector. Much of this has to do with the limited funding the government allocates for research and development, but if we look closely and read between the lines, we will see that funding is the least of our problems.

The Project NOAH initiative hinged on the idea that for us to prepare and mitigate the effects of natural hazards, we needed to improve our capability to create scientific knowledge and integrate it to daily operations. At the time, we already had institutions tasked to do these. But by starting Project NOAH, the then-administration had implicitly admitted that the existing scientific establishment is sorely lacking; in fact, the ad hoc nature by which Project NOAH was setup was indicative of the gaping holes in our institutions. The ambitious scale of the program was unprecedented. Research projects related to natural hazards and disasters were loosely brought together and branded as part of the NOAH program. Although DOST funds the research projects, most were implemented by scientists from the University of the Philippines.

If we were to progress, the government needed to infuse fresh ideas from people outside of the system, people who think outside the box. The establishment did not take too kindly to this; indeed, Project NOAH was met with vigorous opposition. Those against it used—misused, really—the word “mandate” to justify why no one should encroach on their scientific “turfs.” They had drawn lines in their sandboxes, but the winds of change had begun to blow those away.

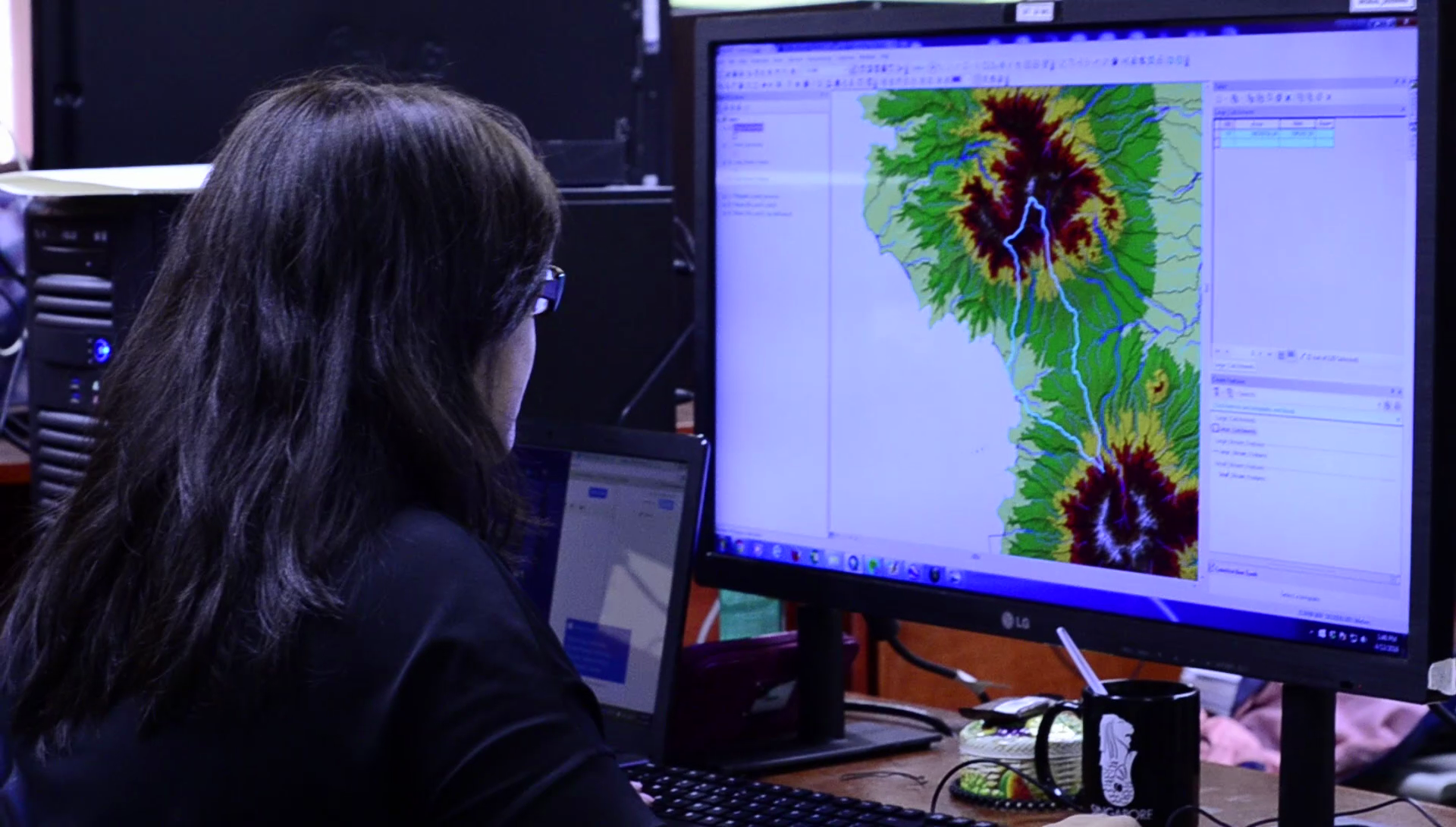

Who are these people anyway, that had the audacity to challenge the system? Front and center were scientists and engineers from the University of the Philippines and the Department of Science and Technology. The objectives laid out were simple and straightforward: provide state-of-the-art maps to aid disaster risk reduction efforts, identify gaps in the government’s operational procedures and then figure out how to bridge it. But the scale and complexity, not to mention the urgency, of these tasks meant that those handful of people could not humanly accomplish what they were asked to do. They needed vast resources: funds to acquire high-tech equipment and get the necessary human resources. Getting the equipment was easy enough. Despite a mindbogglingly complicated and inefficient government procurement system, at least all one needed to know were the specifications. Getting people on board, however, is another story.

That’s where we come in. From a motley crew of project staffs, our numbers grew to eventually become the band of misfits who make up Project NOAH. The thing is, Project NOAH didn’t really exist. It had no funding, nor did it have an infrastructure for its operations. What did have funding were the many different research projects placed under the umbrella of Project NOAH. The integration of all the efforts are visualized mostly through the NOAH web portal, but this only represents a portion of the total work done. So, without any system in place to absorb the manpower for a nationwide-scale research program, the government had to improvise. The common practice then was to hire people as contractuals with a no “employer-employee relationship” provision in the contracts, putting us in a gray area between being a consultant and an employee. This meant that they didn’t want us to be employees so they could deny us whatever benefits the law had prescribed for employees. But then our day-to-day work was directly managed by our supervisors, so we weren’t really consultants. It was a blatant violation of our labor rights, even more so for the people who go out to the field in extreme weather conditions, and to those fly in cramped airplanes to operate the high-tech mapping equipment; they go out without the benefit of any hazard pay. The institutions that funded and housed us had skirted their obligations, getting all the benefits from our work without giving back anything. Worst of all, this has been a rampant practice among many government agencies long before Project NOAH even started.

Despite this, in some ways it still felt like things were finally looking up. The national government appeared very willing to invest heavily on scientific research and development. Major funding was made available, and government executives were forcing the release of erstwhile inaccessible government scientific data, much to the chagrin of those in the establishment.

At the time, we didn’t have the people with technical skills to do a lot of what had to be done, so they had to be trained. The collective knowledge and experiences gained were invaluable. It meant that, as a nation, we were actually getting back a lot more from what had been spent. Sobrang sulit na, ‘ika nga.

These people were not mere machine operators. They gather data using sophisticated technologies and techniques, then turn these to useful information. Unfortunately, these high-tech and specialized skills have no room in the industrial sector because the Philippines doesn’t have industries that can take them in. We were building a mass of highly skilled people with nowhere to go to.

What our country sorely need are scientists and engineers, people who can create new knowledge and build new technologies. But when an employee of our government’s science and technology department declares that these people are merely “project staffs” and not “scientists,” it puts a damper on our young people’s aspirations to have a career in science in this country. Indeed, if people from an institution that is supposed to promote science and technology doesn’t respect the people who actually do science and technology simply because they aren’t “regular employees,” then where does that leave us? This may not be the official policy, and this may even be a view shared by the minority, but the mere presence of such attitude in a scientific institution is simply befuddling. If we weren’t, who then can be scientists? Only those with titles appended to their names? Or those with official-sounding designations? This is such an elitist worldview.

Sadly, this culture and mentality permeates deeply in our institutions, and the factitious nature of our science community—particularly magnified in the geosciences—exacerbates this problem. “Membership” in a “mandated” institution provides one with an aura of exclusivity, as if it gives one exclusive rights to do scientific research. With a virtual stranglehold on government funding, they are very capable of exercising this “authority.” Science to them is a zero-sum game. No one is “allowed” to do any research without their blessing, especially if it’s within their designated “mandate.” Data is not released to the public because they think “panic” might ensue, therefore, people have to be “vetted” before they can be allowed such privilege. How then can those who live far away from Imperial Manila access these knowledge? Do they need to go to the Capital, bend a knee and swear fealty first?

Such is the life of a common-folk in the science community. There is no proper employment status, and no prospects of having one unless we swear fealty to one of the fiefdoms. University employment is also bleak, as there are limited spots for professorships and even fewer for research positions. The only other options are the private sector businesses and industries, or jobs overseas. We do scholarly work, gather and process data, and publish in scientific journals. In short, most of us pretty much do the work of scientists. What else does one have to do to be a “scientist?” Does a king have to put a sword over one’s shoulders first?

One does not need a job in science to be a scientist. Unless you have a billion peso trust fund at your disposal, a career in science is needed to sustain such work. That being said, having a job in science doesn’t make one a scientist. A lot of people confuse the two. Just because someone may be employed as a faculty in a university, or has a research position in a science agency, it doesn’t mean they can claim to be scientists. In an ideal world, these job items are filled with people doing actual science work. Unfortunately, ours is a world far from ideal. A lot of things prevent people from doing their work, either because of limited resources and funding, restricted access to scientific data, institutional rivalries, or a combination of these. Ultimately, our society suffers.

Technological advancement alone is not progress. Attitudes have to change with it. We need an egalitarian society that distributes resources equally, one that is not beholden to the whims of a few technocrats, acting like the colonial masters of old who think that knowledge is theirs to give or withhold. These antiquated views have no room in our institutions already struggling in their transition to modernity.

Perhaps one day, ours will be a society that welcomes wide-eyed kids from the countryside who dream of having careers as scientists.