Paying tribute to the martyrs of the Hacienda Luisita Massacre, Luisita farmworkers and a thousand of their supporters stood right where the bloodbath took place exactly ten years ago – in front of the walls of Gate One of the Central Azucarera de Tarlac, the reputed mill of opulence and political power of the Cojuangco-Aquino clan.

These wide walls conspicuously visible to motorists passing through the expressway’s Luisita exit brandished a row of outdated AQUINO-ROXAS 2010 electoral ads, which for those familiar with what transpired on the same spot on November 16, 2004 could certainly have taken an altogether different meaning. Campaign lines such as “Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap,” could very well have been read to mean: “Vote for us, we actually killed peasants here!”

But for a few hours coinciding with the tribute, these walls were transformed into an open art gallery.

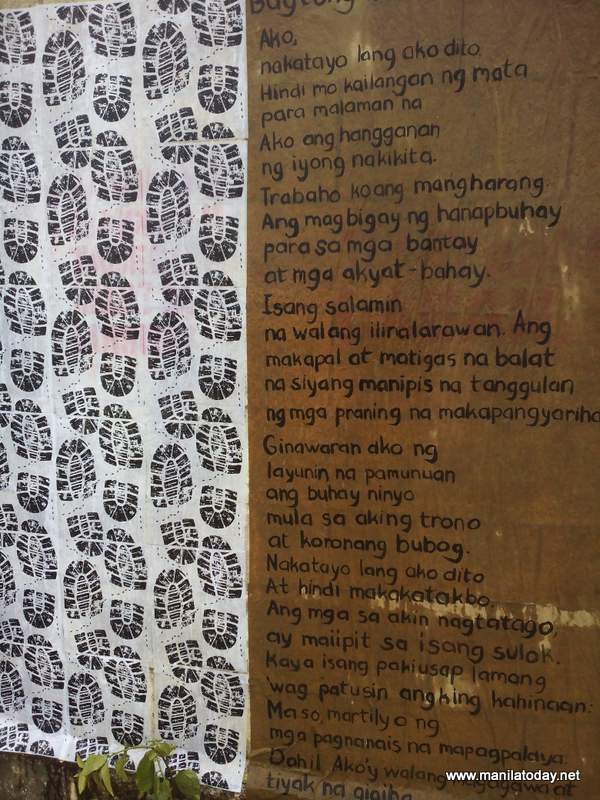

Human rights group Karapatan posted 5-feet high portraits of each of Luisita’s seven martyrs. Volunteers for Jes Aznar’s #HLMX project installed large-scale reproductions of the photojournalist’s works from his seminal reportage of the 2004 Luisita strike. The outdoor exhibit filled a hundred meters of the walls with graffiti, poetry, wheatpaste murals, and installation art, punctuated with the farmworkers’ own scathing protest slogans. The calls, mostly in bright red stencil marks, held the state and the Cojuangco-Aquinos criminally liable not only for the massacre of a decade ago, but for the continuing repression, sham land reform, and violent landgrabbing being perpetrated against the toiling folk of Hacienda Luisita under the current Noynoy Aquino regime.

What appeared to be an impromptu wall display for most of the participants of the gathering was actually part of an ongoing project initiated by advocates of the Luisita Watch network. The main segment of the wall works was curated by Antares Bartolome with contributions coming from artists Salvador Alonday, Emmanuel Garibay, Buen Abrigo, Frances Abrigo, and Leeroy New, among others.

An enormous multi-colored tent, similar to what the sugar workers used as shelter in the historic picketline of 2004, was raised up to the sky. The sight of farmworkers’ calloused hands holding up the lone bamboo pole to prop the tent up once again after ten long years was enough to bring tears to the eyes of anyone aware of the Luisita farmworkers’ poignant saga. The same scene, with the mass of people assembled in solidarity amid powerful wall images and writings, is likewise a foreboding enough sight to make the people’s enemies tremble with fear.

A couple of hours after the huge crowd of marchers had left the site, or at around 3 pm (the exact hour when the massacre occurred 10 years ago) the walls had already been whitewashed by the mill’s security personnel, destroying all of the artworks.

Leeroy New, whose relief installation literally stood out among the artworks on the walls, can now only provide ‘mere photographic evidence’ and descriptions of his work: “We attached arms onto the exterior walls of the Central Azucarera de Tarlac, where the massacre took place. The arms appear severed or that the bodies attached to them were buried within the tomb-like concrete.”

A view of New’s buried bodies unearthed forgotten stories. The Hacienda Luisita massacre was the violent dispersal that killed seven and wounded dozens of others when police, military and other state forces opened fire on the striking sugar workers. This about sums up the whole incident for most. New’s macabre figures seemed to plead to make people remember more of the massacre’s grisly details.

Subsequent fact-finding reports attested that some of the dead were found mutilated. Some victims were believed to be only wounded but were either left for dead or summarily executed. The lifeless body of the youngest victim, 20-year old Jhaivie Basilio, was found by his mother Violeta hanging on a barbed wire fence bearing torture marks. Another victim, 30-year old Jessie Valdez sustained a single gunshot wound on his right thigh, a wound that should not have been fatal.

The day before the massacre, the police and military already took over the nearest hospital also owned by the Cojuangco-Aquino family. Some wounded survivors who were rushed there claim that instead of being given immediate medical attention, they were hit with nightsticks and threatened with arrest by state security forces.

Incidents of pursuit, mauling and arrest of more than a hundred sugar workers during the dispersal largely remain unstated. A number of the detainees were strikers from Luisita, but most were sakadas or undocumented migratory farmworkers hired by the Hacienda Luisita Inc (HLI) management from Northern Luzon and the Visayas for their cheaper labor during the kabyaw or milling season. The arrest of the sakadas, or of so many non-Luisita residents, gave actual figures to the “outsiders” referred to by BS Aquino in his privilege speech as Congressman only a few hours after the massacre.

These so-called external “agitators” were consequently blamed by Aquino and his kin for instigating unrest in their otherwise peaceful sugar estate. Witnesses said that some of the sakadas, who were not even involved in the picketlines, were rounded up in their barracks or makeshift sleeping quarters. Women detainees also reported that they experienced sexual harassment under police custody.

Some of New’s arm pieces were installed on the galvanized iron gates of the sugar mill, with the hands and the main mass of bodies appearing to emerge from the adjoining cement walls, as if in an attempt to escape. This most disturbing image brought to mind the lingering story of the sakadas believed to have been shot in the melee, but have all mysteriously disappeared after the incident.

A review of Senate investigation transcripts will reveal witnesses’ claims that the first casualties of the November 16 dispersal were an infant child and the sakada father. The child, according also to the consistent accounts of survivors and witnesses from the different barangays in Luisita, was killed by the heavy bombardment of teargas in earlier attempts to disperse the strikers. In an angry fit, the sakada father confronted the police and military with the kampilan used to cut sugarcane. This sakada is said to have been the first casualty of the gunshots.

The video Aklasan, a short but forceful documentary of the 2004 Luisita strike, pays tribute to the father and child as among the confirmed victims of the massacre. A poem by Michael Coroza, featured in the landmark anthology Pakikiramay, specifically highlights this sakada infant’s sad narrative. Even initial media reports counted the massacre victims at 14. The seven martyrs who were all from different Luisita barangays are but the documented victims. With the heavy and prolonged gunfire, more are believed to have been killed from the ranks of the nameless sakadas.

Ten years after, more buried stories still find escape. Immediately after the massacre, the sugar mill was said to have oddly discharged dark billows of smoke even when the strike had already paralyzed production for several days. People said that the missing sakadas were dragged inside the compound walls and burned in the incinerators. In Luisita, this morbid open secret is corroborated only by wild ramblings of village madmen who confess that they have conspired to carry out this horrifying whitewash. But others in complete indignation may even look you in the eye and swear that that was not the first time that the lords of Luisita burned their salvage victims inside the sugar mill.

On the instant whitewash of the HLMX wall works, Leeroy New remarked that “the value in these kinds of works is proportionate to the desire for their destruction,” perhaps without half-suspecting the range of brutal memories that the mere sight of his installation might have invoked. We are not even talking about the deaths in Luisita in the decades before the massacre, or the subsequent spate of extrajudicial killings which claimed the lives of more union leaders and peasant advocates, a village chairman, a city councilor, a priest and even a bishop.

New and company’s outdoor exhibit became ephemeral not because the artists have not considered heat, rain, erosion or any of these incidental elements. The works are now gone, deliberately destroyed, because the very visions ignite deep-seated anger borne of a decade-old massacre and longer injustice. The intense representation of the oppressed in a stance of militant defiance is among the themes that will never be tolerated by the oppressing class enemy. Under Aquino’s cacique dispensation, these themes can only court media black-outs, state censorship and ridicule from a monotonous yellow horde brainwashed and bought by bourgeois authority. The decade of injustice in Hacienda Luisita that Leeroy New, et al represented in these artworks is the actual, constant subject of whitewash within the courts and other institutions controlled by tyrants.

“The enemy moves fast,” New finally observed. The artists could always point to the consoling fact that along with the artworks, the atrocious campaign ads themselves have been whitewashed as well. At any rate, the more reassuring fact is that BS Aquino and his PR cabal are running out of tripe and spin to evade the latest of the regime’s series of epic plunder scandals and foul-ups. The people are rising. The enemy is in fact losing speed.

For updates on the situation of Hacienda Luisita farmworkers, visit www.luisitawatch.wordpress.com. To view Jes Aznar’s #HLMX photos, visit www.hlmx.org