“Yan ba yung tokhang? Tokhang ba ang ibig sabihin niyan?” an old man asks in a whisper. It was the height of the war on drugs, and people only spoke of the ensuing deaths in hushed tones. Archie Oclos was then working on a mural on an unfinished 10 x 18ft wall that he decided to fill with images of guns.

He nods at the man, who continues, “Alam mo ba, dito sa Krus na Ligas, may tatlong taong pinatay.” Conversations like this about social issues – especially with and among ordinary people – are what Archie aims to encourage with his street art. On that day, he was not disappointed.

“Nakuha niya!” Archie exclaims, but not delighted that tokhang has entered our lexicon. A portmanteau of the Bisaya words toktok (knock) and hangyo (plead), it now easily conjures images of men barging into homes, summarily executing the suspected drug user or pusher. It is the latter who makes a plea. Only the poor die, and cries for justice for the slain husband, father, son, brother, uncle, or grandfather – someone’s beloved – are easily drowned out by four syllables and a shrug: “Nanlaban, eh.”

“Nakuha niya!” Archie exclaims, because to him this confirms that the masses can, in fact, appreciate and understand his kind of art. “Hindi mo pwedeng sabihin na hindi nag-iisip yung mga masa. Nag-iisip talaga sila. Alam nila kung paano intindihin ang mga bagay,” he shares, his tone ever more emphatic.

The same deep respect for the common folk is palpable in the way he mounted his show at the Kanto Gallery, a solo exhibit called Tutuldok. He brings his art indoors this time, but as Karl Castro points out in his introduction, Makati Cinema Square is hardly the haunt of art patrons and critics. Instead it is a space for the working class, an old mall in the busy Pasong Tamo district – home to several stalls of ukay-ukay, a few gadget repair stores, a thrift bookshop, a Jollibee.

Inside Kanto are seven paintings, a deceptively small collection. But each piece is almost too much to take in, and will draw a sigh, a gasp, if not tears, once one realizes what it is about.

The artworks were arranged Baroque-style. Every painting on one side has a counterpart on the other, the choice of colors, panel size, and painting style and composition lending a sense of balance, and their symmetry betraying the chaos and madness in the milieu being portrayed.

In the first piece, Archie shows the cuffed hands of someone begging for life. Facing this is an image of the small assemblage of metal that becomes all-powerful, when held by men who want to play God. Fittingly, rays of light emanate from it.

On the left side of the main wall are two paintings set in the city. A part of the pavement, splattered with red. Beside it, a glimpse of a dark alley between rows of slum dwellings. To the right are scenes from the country. There are rice paddies and nipa huts (bahay kubo) at the foot of the hill, a scene that one could perhaps mistake for a relaxing pastoral view, until the eyes move to the next painting: a cluster of sugarcanes, some with blood-stained leaves. According to Archie, the bigger piece was inspired by the development aggression driving Aetas away from their homeland in Pampanga, and the smaller, by the struggle in Hacienda Luisita, where farmers and farmworkers had been killed in their fight for land reform.

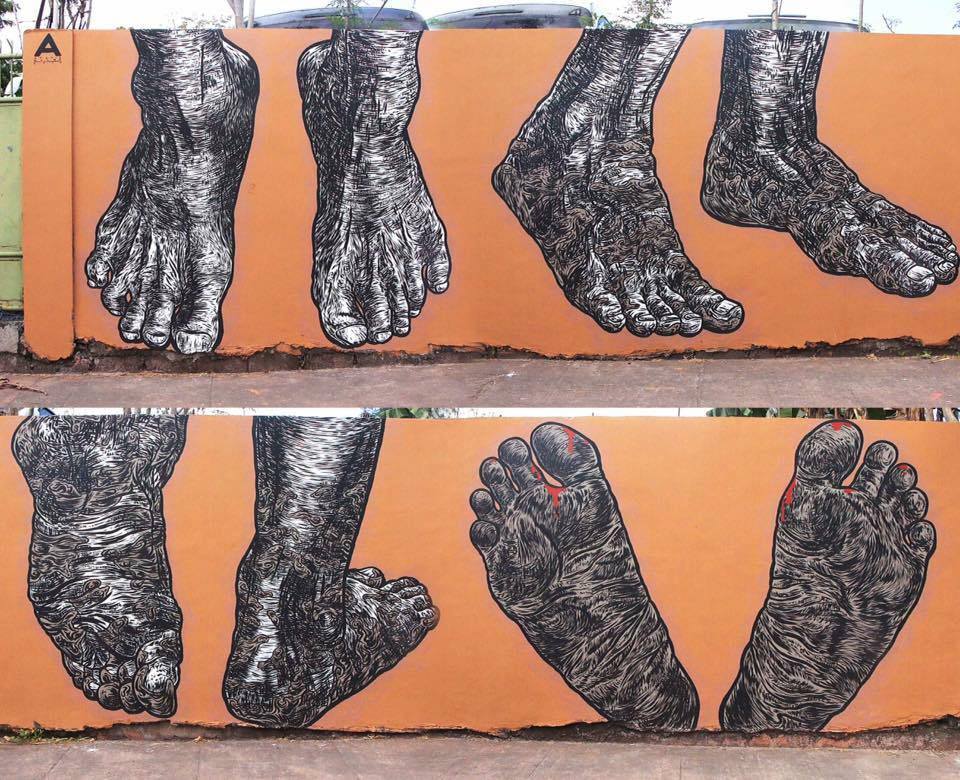

In the middle is a piece that could pass for a wallpaper, with its bunch of roses, peonies, and stargazers flanked by ornate candelabra. But one looks up, sees the feet of Jesus nailed to the cross, and realizes that the flowers belong in a funeral. There is an epiphanic moment when experiencing each of Archie’s works, and one cannot look at the painting the same way again.

If the inside of the gallery feels grim, the mural of carabaos in the hallway outside gives hope, and Archie was conscious in depicting them as strong, dynamic, and resolute – not just as the still and gentle beasts of burden most Filipinos know them to be.

The mastery of technique and composition shown in each of the artworks is noteworthy, but not surprising – Archie is a painting graduate of the UP College of Fine Arts who has won many competitions. Years of being a street artist have also instilled in him a remarkable command of his media: he opts for simple colors, and can finish a painting in three hours, using a small paintbrush to capture the most minute detail. In fact, he says that visual execution is the easiest part. “Yung magpinta ng subject, madali yun eh. Pero yung kung paano siya magkakaroon ng kurot, yun ang mahirap!” Archie shares animatedly.

Too, he is not keen on pursuing perfection: “Kapag naka-capture mo sa art yung mga imperfection, nagiging natural yung work mo eh… Kaysa yung, sobrang pulido ng lines, sobrang ganda ng vector, sobrang realistic. Parang minsan may detachment ka sa artwork at saka sa sarili mo rin.”

What takes up more of his time, instead, is conceptualization, to be able to leave a lasting impression: “Kasi sa street art di ba, pinakamatagal na yung 3 seconds na makita yung wall. Kasi dumadaan ka lang eh. So, ano yung idea na kayang mabaon ng tao sa loob ng 3 seconds? Kaya yung mga gawa ko, sobrang simplified na. Pero ang hirap talagang isipin, parang logo.”

How can artists depict violence among people who seem to have grown accustomed to it? How can they document the horrors of our times, and still tug at heartstrings? How can they inspire humanity to not look away, amid the continuing violence in the cities and the countryside? How can they speak of the unspeakable?

Archie Oclos understands the challenge, and that understanding informs his art. He invites us to look, and look we must.![]()