Seventy-five (75) years after the end of World War II, it is again timely to also remember a German connection in instilling militarism, fascism and racism into the minds of Filipinos – at least segments of society – during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

But to put records straight, it must be emphasized here that in fact it was Filipinos who, after Chinese, Korean and Malayan civilians, suffered most and paid dearly between December 1941 and mid-1945. Approximately 1.2 million Filipinos lost their lives while actively or passively resisting Japanese militarism. And next to Warsaw, it was Manila that was the most severely damaged capital during World War II.

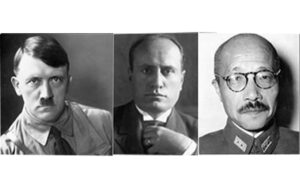

Japan then formed an integral part of the self-acclaimed Axis powers which included Benito Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany. The axis Rome-Berlin-Tokyo was envisioned as a strategic alliance in the pursuit of establishing a world-wide empire under the aegis and hegemony of these “master races”. Similar to the Nazi ideological construct of “Lebensraum” or “Blut und Boden” (blood and land), Japanese Prime Minister Matsuoka Yôsuke announced the concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in August 1940. (1) The idea of Japanese superiority over other Asian races had been expounded as early as the late nineteenth century and steadily grew after Japan, in 1905, became the first Asian country to defeat a Western power – Russia. In the words of historian Peter Duus, the ideology of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere allowed the Japanese to view themselves as “leaping from the baggage train of history into its vanguard.” (2)

Ultranationalist groups believed that the moral purity of the Yamato race and Japan’s unique ancestry as descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu entitled the Japanese to such a leadership role in fighting Western colonialism and imperialism in Asia. Japanese leaders used the Co-Prosperity Sphere in its propaganda for the people both in Japan and in other Asian countries. They set up Tokyo-controlled puppet-governments with local leaders shallowly proclaiming “independence” and pursued a program of “Japanization” on the people with little or no regard for local customs and beliefs. Tokyo’s propaganda, however, initially led many of the peoples of Southeast Asia to view the Japanese as liberators while anticipating a brighter future under their tutelage – a conceptual fallacy, to say the least.

As close allies, the Nazi fascists and Japanese militarists were bound together by a congenial concept of supremacy and hegemony. This concept in turn was propagated in the Philippine setting by relying on extreme right-wing elements linked to the “old motherland” Spain. Back in 1936, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering had already observed that “Spain is the key to two continents.” By controlling Spain, the Nazis felt they could control both Europe and Latin America. They realized that to dominate Ibero-America through Spain, they had to crush the Spanish Republic. Therefore, the Third Reich closely cooperated with officers of the Spanish Army to bring General Francisco Franco to power in 1936 (3), using the Falange of José Antonio Primo de Rivera as their base of operations in Spain, and as the vehicle for penetrating Ibero-America. The Falange Exterior, a Spanish-speaking division of the Foreign Organization of the German NSDAP, was created for this purpose. Geographically dominating the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic and “flanking” France, Spain still wielded tremendous influence in Latin America through the strong cultural and economic ties between the Spanish and Latin American aristocracies. In addition, the profound Catholic influence in both Spain and Latin America, augmented Spanish clout in that part of the world.

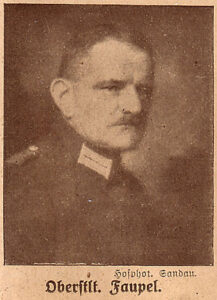

To utilize Spain’s geopolitical influence as a tool for Nazi imperial designs, the Third Reich turned to General Wilhelm von Faupel and installed him as the new head of the Berlin-based Ibero-American Institute. Von Faupel had been engaged on several war fronts. For the German Kaiserreich he fought in Africa and China. He later turned into a bitter opponent of the Weimar Republic, and readily accepted the Nazis as the antidote to German democracy. Von Faupel was generally known as the “I.G. General,” referring to the German chemical company I.G. Farben which became one of the major financial supporters of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Also, he already had significant experience in Ibero-America. In 1911, he joined the staff of the Argentine War College in Buenos Aires; in 1921, after World War I, he was the military counsellor to the Inspector General of the Argentine Army; in 1926, he had a high military post in the Brazilian Army, and later in 1926 became Inspector General of the Peruvian Army. (4)

Rejecting royalist and Catholic sectarian rightist parties, von Faupel and the Nazis settled on the Falange as their chosen vehicle for gaining dominance over Spain. Von Faupel then proceeded to direct the construction of the “Falange Exterior” as the fascist Fifth Column movement throughout the Spanish-speaking world – including the Philippines. Spanish fascists were trained by the Gestapo to work for the Axis. There were schools for Spaniards in Hamburg, Bremen, Hanover, and Vienna. Graduates were commissioned as officers in the Spanish Army’s Intelligence Service, the SIM. As the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines in late 1941 approached, the Nazis had earlier arranged for the Spanish Falange to pave the way for the Japanese takeover of the Philippines. General von Faupel appointed José del Castaño regional chief of the Falange Exterior for the Philippines and Spain made him her Consul General in the Philippine capital where he worked together, among others, with Enrique Zobel and Andres Soriano, two of the wealthiest Spanish businessmen in Manila. Zobel, who held the post of “consul” of the Franco regime, claimed to be Franco’s personal representative in Manila.

“The Manila to which José del Castaño sailed in the winter of 1940 was in many ways more fervently Falangist than Madrid itself”,

wrote Allan Chase in his book Falange – The Axis Secret Army in the Americas (1943), and he continues:

“To the utter amazement of the new Consul General and the new Regional Chief, the five branches of the Philippines Falange Exterior put on a show for him that could not have been duplicated for sheer numbers in Madrid in 1936. The affair took place in December 1940 at a Manila stadium – secured at a nominal rental from the Spanish businessman who owned it. First, to start the festivities, the five-and six-year-old youngsters in uniform lined up in military formation and started to march across the field to the music of a brass band. They wore uniforms, these little fellows-blue shirts and shorts and Sam Browne belts like the Exploradores (Boy Scouts). But they were not Exploradores, they were Jovenes Flechas (Young Arrows) de Falange. The uniforms were, for the time being, somewhat alike. In the beginning, the Jovenes Flechas were taught how to march, how to sing Cara al Sol, the Falange hymn, and how to give the brazo en alto (upraised arm) salute when they shouted ‘Franco! Franco! Franco!’ Later, they would learn how to shoot, like the older ones. Following the little fellows came the Seccion Femenina de la Falange de Manila. This contingent was an utter surprise to del Castaño. It embraced everything from five-year-old preschool girls to nurses in their teens to matrons built along the lines of assault tanks – all of them in immaculate blue uniforms, marching behind the banners of the Falange and Imperial Spain, saluting smartly with the approved stiff arm, carrying themselves like women fit to grace the beds and the kitchens of the new conquistadores. When the Falange thrust its five arrows over the horizon, the rich Spaniards in the Philippines saw in them the pointers to the type of Spanish Empire their fathers had really known.” (5)

The policy pursued by del Castaño was best summarized in his own words:

“Our Fascist brothers in Japan,” the Consul General used to say, “are united with us in the common struggle. When they strike, we must help them. When we strike, they will help us.”

And this both sides did. The most effective way in paving the way for and assisting the Japanese was the infiltration of and eventually paralyzing – at least substantial parts – of the Philippine Civilian Emergency Administration (C.E.A.). The mastermind behind this scheme was no less than war-experienced General von Faupel who knew too well the value of divisionary tactics and that modem total war is the war of the organized rear. Writes A. Chase:

“Civilian defense organizations may not be as vital as armies, but they are necessities. Manila taught the world what a menace a city’s civilian defense organization becomes when it falls into the hands of the enemy. Thanks to the Falange – and its regional chief, Spanish Consul General José del Castaño – the rear had been completely disrupted. The civilian defense organizations, created to bolster civilian morale and to counter the effects of enemy air raids, were accomplishing just the opposite. At three o’clock on the afternoon of January 2, 1942, the Japanese marched into Manila, their military tasks having been lightened a thousandfold by the effective Fifth Column job within the city itself. (…)The total number of Falange members in the Philippines is known to very few – a trustworthy estimate places it at close to 10,000. Had only half of the estimated ten thousand calculating Falangistas moved in on the civilian defense organization, the Axis purpose would have been accomplished. The Falangistas who went into civilian defense work all received special training from Falange chiefs close to del Castaño himself. (…) The Falangistas in the Philippine Civilian Emergency Administration were a trained Axis Fifth Column army, ordered to their posts by the Nazi general who sat as Gauleiter of Spain, and directly responsible to the chief liaison man for all Axis espionage in the Archipelago.” (6)

Despite the fact that the U.S. government already in mid-June 1941 had given the governments of Germany, Italy and Japan until July 10 to close their consulates on United States soil and territories, José del Castaño temporarily took over the consular duties of all three closing consulates in Manila.

“Not publicly announced, but nevertheless just as official”,

notes A. Chase,

“was José del Castaño’s appointment after July 18, 1941, to the most important Axis espionage post in the Philippines. The Falange chief was made the top liaison agent of all Axis undercover work in the Islands. His consulate-general offices became headquarters, post office, and clearing house for the entire Axis spy network. (…) In New York, in London, in Moscow free men and free women mourned the tragedy that had befallen Manila. But in Granada, Spain, on January 5, 1942, there was a joyous Falange celebration. Pilar Primo de Rivera, the psychopathic sister of young Primo and the chief of the feminine section of the Falange, brought the crowd screaming to its feet. In the name of the Philippine Section of the Falange Española (…), Pilar Primo de Rivera accepted a formal decoration from the Japanese Government – a decoration awarded to the Philippine Falange for its priceless undercover aid to the Imperial Japanese Government in the capture of Manila and for a host of other services. Among the latter were the fleets of trucks and busses the Falange had ready and waiting for the Japanese invasion troops at Lingayen, Lamon, and other points. The cheers in Granada had hardly died when the Archbishop of Manila issued a pastoral letter calling upon all Catholics in the Philippines to stop their anti-Japanese activities and to co-operate with the Japanese in their noble efforts to pacify the Archipelago.” (7)

This cooperation, in fact, culminated in the creation of Filipino volunteer armies such as the Makapili (Makabayang Katipunan ng mga Pilipino – Patriotic League of Filipinos), the “Peace Army” and the Bisig-Bakal ng Tagala (Iron Arms of the Tagalog Women). To help win the support of the majority Christian population and elite officials, the Japanese Army General Staff even created a special Religious Section made up of Christian clergy and laity from Japan. The members of this section visited various parts of the country to say mass and hold services in local churches and facilitated the release of detained religious personnel. Bishop Taguchi of Osaka later joined the section staff and actively led the appeasement campaign directed at the Philippine Catholic Church. Through the policy recommendations of Bishop Taguchi, the Japanese military administration sought a comprehensive agreement (concordat) with the Vatican that would have addressed contentious demands such as the Filipinization of the ruling hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the regulation of church property, and the regulation of educational curricula. (8)

As far as the Spanish community then residing in Manila was concerned, it was by no means homogenous, but instead at loggerheads with each other due to the Spanish War. There existed several camps which confronted each other: leftist republicans, Basque hacenderos and Falangistas backing blindly the Franco Government. As regards the wealthy families, whose ideology was strongly conservative (therefore tilting in favour of Franco), their allegiance was split after World War II started. Though no harsh conflicts among the Spanish community arose, eventually leading to violence, the atmosphere created, however, prevented the community from acting as one. Opting for Filipino citizenship was one way of protecting ones properties, being in line also with Quezon’s plan to promote a Filipino upper class. (9)

Militarism, fascism and ideologies glorifying racism and superiority were intrinsically linked with and brutally executed by the Axis powers. Germany and Japan clearly shared the concept of a “natural ruler” and “master race”. And it was in the Philippines were Nazis and Falangistas alike were instrumental in transplanting fascism, which after the Japanese invasion fused well with Tokyo’s own concept of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The legacies of this dark chapter in history could nevertheless be felt decades later. As regards the Philippines: In contrast to the collaborating national elites who were given amnesty after the war, surviving Filipinos who had joined the volunteer armies on the Japanese side served prison terms and were treated as social outcasts in their local communities. And those who bravely fought the Japanese, while simultaneously despising all kinds of foreign interventions – especially formations like the Hukbalahap – were shabbily treated as “bandits” and “terrorists”.

And in the post-war setting in Europe, no serious attempt was made to “de-Falangize” the Iberian peninsula. Franco and his fascists remained in power in Spain until 1975. Portugal remained under the control of the fascist dictator Salazar for decades after the war. And the decisive influence of Latin American fascists in the decades following the war (including collaboration with elements of U.S. intelligence) is a matter of public record.

===

Footnotes & Sources

1) The justification put forth for Japanese expansion and its construct “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was as follows: “”In order to realize world peace, it seems to be the most natural step that peoples who are closely related to one another geographically, racially, and economically should first form a sphere of their own for coexistence and co-prosperity and establish peace and order within that sphere, and at the same time secure a relationship of common existence and prosperity with other spheres. (…) The countries of East Asia and the regions of the South Seas are geographically close, historically, racially, and economically very closely related to each other. They are destined to cooperate and minister to one another’s needs for their common well-being and prosperity, and to promote peace and progress in their regions. The unification of all these regions into a single sphere on the basis of common existence and assuring thereby the stability of that sphere is, a natural conclusion” – see: Peter Duus, Japan’s Wartime Empire: Problems and Issues, in: Peter Duus / Ramon H. Myers / Mark R. Peattie (eds.), The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931-1945, Princeton 1996.

2) Ibid., p. xxiii.

3) Thousands of trained Reichswehr troops were used as advance troops of the “Legion Condor”, organized by von Faupel and other Nazi comrades-in-arms to “rise Spain to her old glory” and aid the fascist and Falangist Franco camp in its fight against die Republican forces, massacring along its way civilians in droves and ultimately pulverizing Guernica ino ashes. These Condor Legionaires had an official marching song which ran as follows:

“We whistle high and low,

And the world may praise or blame us.

We care not what they think

Or what they’ll one day name us.“

For details see: Allan Chase, Falange – The Axis Secret Army in the Americas, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1943.

4) Reinhard Liehr / Günther Maihold / Günther Vollmer (Hg.), Ein Institut und sein General – Wilhelm Faupel und das Iberoamerikanische Institut in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert, 2003.

5) A. Chase, op.cit., pp. 38, 39.

6) Ibid. – especially chapter 2: Falange Es España, or What Really Happened in Manila, pp. 32-50.

7) Ibid. – In this context, the author notes, even the academic world was not spared from Falangist thoughts and ideas. Father Silvestre Sancho, Rector of Manila’s prestigious University of Santo Tomas, had visited Madrid in search for a person who could qualify to chair the newly created “Hispanidad” department. The choice was no less than Generalissimo Francisco Franco, anticipating a revived Spanish Empire which would embrace Manila and smoothly coexist with the Axis powers.

8) Ikehata Setsuho / Ricardo Trota José (eds.), The Philippines Under Japan: Occupation Policy and Reaction, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1999.

9) Florentino Rodao, Ph. D. (Universidad de Tokio), Falange en Extremo Oriente, 1936-1945, in : Revista Española del Pacífico [Publicaciones periódicas]. Nº 3, Año 1993; Florentino Rodao, Spanish Falange in the Philippines, 1936-1945, in: Philippine Studies Vol. 43 (1): 3-26. In Tagalog: “Ang Falange sa Filipinas, 1936-1945” (transl. by Diosdado R. Asuncion), in: Ferdinand C. Llanes (ed.), Pagbabalik Sa Bayan. Mga Lektura sa Kasaysayan ng Historiyographiya at Pagkabansang Pilipino. Manila: Rex, 1993, pp. 126-154.