The war on drugs in the Philippines went on for six months before it was ordered halted on January 29 by President Rodrigo Duterte and on January 30 by his Chief of Philippine National Police Ronald Dela Rosa. The impetus was the kidnapping of South Korean businessman Jeck Ick Joo in Angeles City and murder inside Camp Crame.

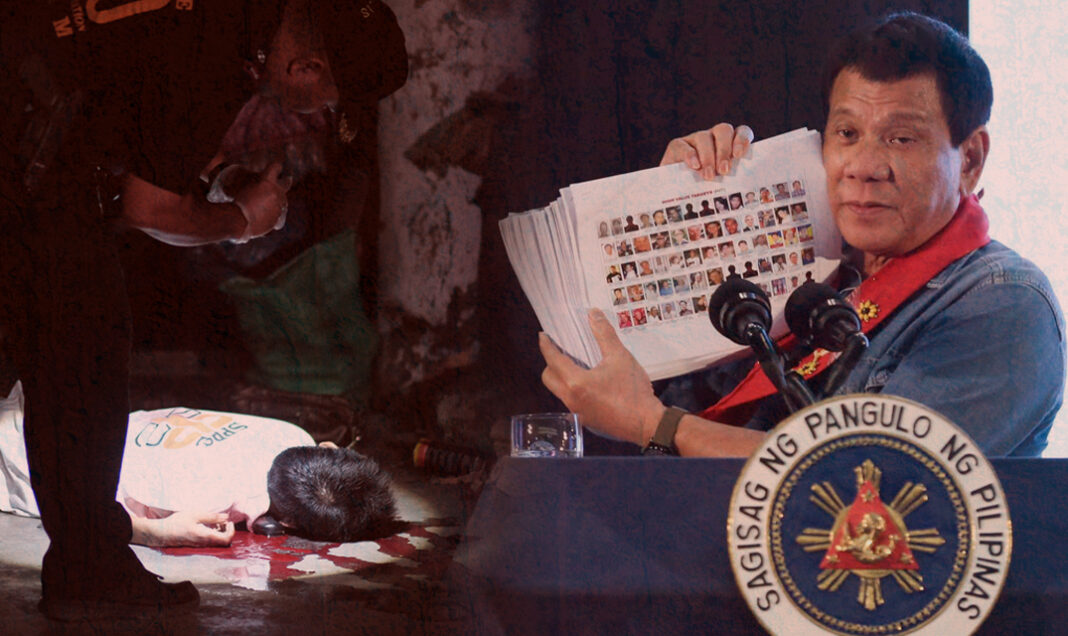

For six months, the police and the vigilantes were on a killing spree; an international wire reported that the police had an almost perfect record of kills in its drug operations. They were on a virtual “license to kill” from the president who said he will back them up, for as long as it is done in the name of the war on drugs. Metro Manila urban poor communities were killing fields at night.

After much doggedness on continuing the uncontrollable rampage of war on drugs that saw the rise of drug-related killings to 7,000, the many incidents of innocents, mistaken identities and collateral damage killed, and various reports of corruption, abuses and crimes of the PNP in the conduct of the drug war, the war on drugs is said to be over. Or suspended, until the PNP is done with its internal cleansing, as Dela Rosa put it. But by the end of January, no more drug operations said Dela Rosa and all anti-drug units at all levels of the PNP would be dissolved said Duterte.

However, at least five more killings in the drug war campaign was reported even after the order to halt the war on drugs.

I interviewed Prof. E. San Juan to give an analysis on Duterte’s bloody war on drugs.

1Could you give your honest assessment on President Duterte’s bloody ‘war’ against illegal drug operations in the Philippines? Do you see any fruitful gain in his drug war?

ESJ: While other countries such as Mexico, Thailand, China, even the U.S., have conducted State campaigns against drug trafficking (not specifically against drug use by individual addicts), they were compelled by popular unrest and legitimized by parliamentary regulations. They are usually accompanied with an educational program of raising public consciousness and mobilizing community involvement. With Pres. Duterte, it has become a personal campaign to prove that his experiment in Davao can work on a nationwide scale. That is fallacious. It is undemocratic because it relies mainly on the coercive self-serving agencies of the neocolonial-oligarchic State. Over six thousand victims, many small drug pushers, even individual users, have resulted. Fear has emptied the streets. But will this stop the big-time drug-lords protected by mayors, governors, local politicians, including military and police officials?

The killing of the Korean businessman in Camp Crame is one proof that the PNP itself, and also the AFP, with the whole bureaucracy, serve as the sociopolitical armature of the drug industry. In short, it is a systemic problem that cannot be solved by State violence. What is the gain? If Davao is safe, my friends in Mindanao say, it is because of fear. While some neighborhoods may be free from drug-trafficking for now, poverty, quasi-feudal warlordism, and booty capitalism with its ethos of corruption remain to serve as a breeding ground for drug-trafficking as part of the fierce class-war among fractions of the ruling class and their retainers. Some say that Duterte wants to be the chief drug jefe, centralizing and concentrating this business for political ends, but for how long?

2Is there any underlying motive behind the drug war?

ESJ: Duterte represents a section of the oligarchy that needs to build a base of support within the police, military and bureaucracy, to entrench itself against the traditional elite. That is one motivating strand. For another, the anti-drug campaign legitimizes the internecine rivalry of one group (with Bongbong Marcos and Arroyo) against others, by claiming to purge the nation of criminal drug lords. It terrorizes impoverished communities. It reinforces passivity of citizens, instilling dependence on authority. These are needed to shore up a moribund system. Despite reports that Duterte’s popularity continues to stay high despite the EJKs, the perceived motive of benefiting the public will resemble the temporary support that the dictator Marcos received in the early days of martial law. This support immediately faded, to be replaced with cynical suspicion, distrust, desperation, and finally massive anger at fascist, authoritarian methods. Mass rebellion is bound to erupt sooner or later.

3It has been observed that there has been unanimously popular support in the Philippines for President Duterte’s drug war, notwithstanding the increasing condemnation of the continuing extrajudicial executions of suspected drug personalities. But could you further explain such continuously popular support for the drug war? Could popular support guarantee the drug war’s success in the long run?

ESJ: Popular support may continue for a while, but economic and moral problems–unemployment, increasing frustration at contractualization, rural misery, brutality against farmers/peasants, especially Lumad and Moro, abuse of women, gays, transgender, etc.; pressures by migrants (Koreans, Chinese, etc), general anomie in a consumerist mall-dominated culture–are bound to increase as corporate competition intensifies and global capitalism suffers a deep recession in the next business cycle.

Is there really popular support in the sense that the impoverished barangays, residents in Caloocan, Tondo, etc. are mobilized to help the PNP? This is doubtful. Even if there is such a show, the authoritarian/patrimonial habits and folkways (embodied in Duterte’s whole performance style) militate against the precarious show of support manipulated in social media, etc. Can the drug war generate more jobs, increase salaries and pensions, lower costs of health care and education, etc.? Can it provide jobs for demobilized insurgents, Lumad and Moro, and for thousands of drug-addicts in need of rehabilitation, etc.?

4Do you honestly believe that the success of the drug war in the Philippines is guaranteed when allegedly petty drug pushers and users are being summarily executed and when historical and sociological roots of the drug problem are being obscured? Do you also believe that these senseless killings would solve the drug problem?

ESJ: This is a rhetorical question. But the assumption that it is a success needs to be questioned, since no big drug lords and their protectors in Congress and the bureaucracy have been indicted and jailed. So it’s successful in killing thousands, but let’s see if in the next five or ten years, we will not experience a resurgence of drug trafficking, thanks to Duterte’s eschatology.

5How do you explain the Left’s concerns regarding what it apparently appeared as the wanton disregard for due process and human rights in the continuing drug war as the third round of informal talks between the Duterte government and the NDFP progresses? Could you also explain the deafening absence of moral indignation against these killings among many people?

ESJ: In our feudalized, patriarchal-authoritarian culture, we tend to follow and obey without question those in government, Church, and other traditional institutions. We rarely question authority in general, trusting in their patronizing aura or conscience if any. The Left so far is refraining from fully questioning the regime’s EJKs since Duterte’s Cabinet has proceeded in peace negotiations farther than the previous administrations. Instead, they have subsumed the issue under the CARHRIHL, etc. in a formalist, un-dialectical manner, leaving the initiative to the GRP. Bongbong Marcos will surprise them later. There is opportunist indignation from the Aquino-Roxas fraction of the ruling class, but not enough from the general public–except from the U.S. media, which functions as diplomatic groundwork for either a coup or more drastic neutralization procedures enabled by the JUSMAG-supervised military and cohorts of disgruntled warlords.

6But do you honestly believe that certain groups and personalities with self-serving political agenda are using the condemnation of the allegedly extra-judicial executions of petty drug users as a credible excuse for their alleged plot to oust President Duterte?

ESJ: Whether they are personally motivated to use it to oust Duterte or not, the question remains whether the EJKs are acceptable under the bourgeois rules of the game. Clearly, the liberal ethical norms of modern states condemn killing without lawful rationale. The neocolonial State can justify everything, as long as the US and international agencies go along with it. However, they would prefer playing according to the liberal-constitutional rules that protect property, life as source of labor-power that produces value, etc. Since we live in a class-divided society, the rights of petty drug-users are nil compared to the rights of big drug lords and their patrons in Congress, PNP and AFP.

7Do you believe that his ‘war’ against illegal drugs and against criminality has diverted public attention from this nation’s basic socio-economic problems that push a huge number of people to use illegal drugs?

ESJ: It has for the middle strata, professionals, etc. But not for workers and peasants whose immediate concerns are livelihood, earning income for food and healthcare, raising their families safely, etc. The petty bourgeois class won’t worry about the EJKs so long as they do not get in the way of their daily business concerns. Because you don’t really have, as yet, a critical mass of civil-society organizations protesting the EJKs, the killings will continue. Yes, to some extent, they are pushing aside much needed discussion of socio-economic problems, but before Duterte’s drug war, was there a huge number of citizens engaged in protesting sexual exploitation of youth and women, corporate mining and destruction of forests, coastlines, etc; and the oligarch’s manipulation of financial institutions and the courts to their advantage? The decadent oligarchy has nothing to offer. Youth enraged take up arms and join the insurgents, while others leave for North America, Europe, the Middle East…..

8What are the serious implications of this nation’s drug war on every aspect of Filipino life and consciousness?

ESJ: For the first time, at least, there is some publicity about the harmfulness of drugs in paralyzing thousands, rendering them incapable of normal work. But whether this will stop drug-use, is another question. Narcotics like mass consumption, malling, wasteful indulgence in pornography and prostitution of all kinds, including selling intellectual property, TV and social media, beauty contests, media happenings and spectacles, celebrities, sports, religious rituals of all kinds–all these are substitutes that perpetuate class, gender, sexual and racial inequities.

9What are the lessons that he should have learned from the failed drug wars in the US, Colombia, Mexico, Thailand, and Indonesia?

ESJ: Each society is unique. Circumstances are different in each time and place, so concrete solutions have to be invented with the cooperation of the grassroots. The only lesson is that violence, State-legalized force, will not eliminate the lure of drugs. As you said, this is a socio-political problem endemic to societies ravaged by the barbarities of global capitalism with its technological efficacy for producing all kinds of drugs to distract the masses from its savage extraction of profit/surplus value from the blood and sweat of millions, esp. those in colonized and neo-colonized countries like the Philippines.

10Could you assess the prospects of the drug war in the Philippines on the basis of the consequences of drug wars in the US, Colombia, Mexico, Thailand, and Indonesia?

ESJ: The prospect is either the awakening of millions of ordinary people to the systemic cause of drug-trafficking in the global capitalist competition for profit accumulation; or the decay and destruction of whole societies by the dominant, industrialized elites of the Global North. In between these alternatives, there will be ceaseless wars of national liberation and anti-imperialist insurgencies until private property of the means of production is abolished, and all forms of exploitation and oppression ended, and only then will human history begin. Maybe this will be the best future scenario for our country.

—

While the Filipino may only have a quick breather before another war on drugs rampage was set to motion, we must try to understand and act on people-oriented, both immediate and long-term solutions to the drug problem. As people who have been forced to witnessed grueling killings and sordid abuses of the national police with the backing of the president in the war on drugs, we must assert and unite as a people how we wanted to end the drug problem in the country.

(Prof. Epifanio San Juan Jr. is an essayist, editor, critic, and poet whose works have been translated into German, Russian, French, Italian, and Chinese. He is a professional lecturer at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) in Manila. He authored countless books on race and cultural studies for which he has been described as a “major influence on the academic world”, such as US Imperialism and Revolution in the Philippines, In the Wake of Terror, Between Empire and Insurgency, and Working through the Contradictions. He received the Centennial Award for Achievement in Literature from the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) in 1999 for his outstanding contributions to Filipino and Filipino-American studies.)